March 2020 – Central banks to the rescue!

The rise of the pandemic across the world resulted in unprecedented support from governments and central banks alike. Whilst furlough and company support schemes were rolled out by respective governments across the western world, central banks also went to town in their levels of monetary easing. The ECB launched a number of pandemic programs extending its quantitative easing policies to €80bn per month and the Bank of England restarted its corporate bond purchase scheme and increased its asset purchase program. As always the most important mover was the US Federal Reserve, buying $120bn per month, including a small amount of corporate debt securities for the first time, assisting some of their big employers, including the likes of Ford.

As we’ve seen in the recent past, the biggest issue with applying stimulus is the difficulty unwinding it. You only have to look to the political capital expended to withdraw the £20 uplift for universal credit in the UK – it is very easy to dole the money out, less easy to withdraw it. That same logic applies to monetary programs too.

October 2021 – The start of the great unwind?

Central banks are at the edge of withdrawing their vast stimulus. The Fed is likely to look to taper their purchases over coming months, with the $120bn monthly purchases going to zero by “mid next year”. The ECB “did not taper”, but “re-calibrated” their Pandemic emergency purchase program. But given the diverse performance of Eurozone economies, the ECB is likely to be one of the last central banks to fully taper their overall purchases in light of their need to support the weaker economies within the euro zone. The Bank of England has said that they will likely raise rates before finishing their buying program, and will look to taper once rates get to a whopping 0.5%. However, at least they will raise rates.

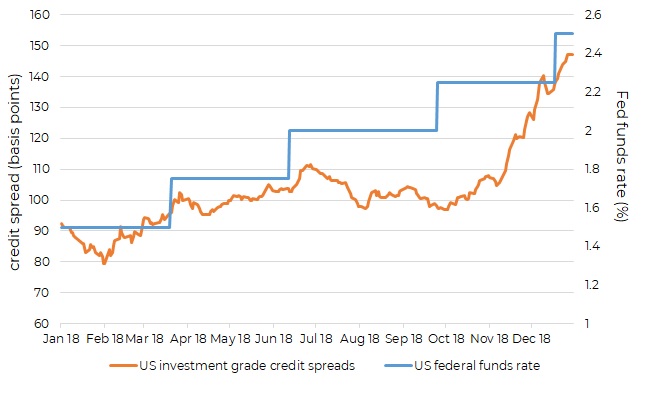

Déjà vu?

US IG credit spreads versus Fed funds rate

Source Bloomberg 02.01.2018 – 31.12.2018

The last time that the Federal Reserve went through a tightening cycle in 2018, the reaction in the risky asset markets (i.e. equity, credit, emerging markets) was quite pronounced, with close to a 20% fall in the S&P 500 in the final quarter alone, as well as credit spreads gradually widening over the year, culminating in a broad sell off, to leave them a sizeable 50bps wider (or 60%) versus where they started the year.

The recent deluge of debt exacerbates the issue

One of the aims of the Fed’s monetary policy was to decrease the cost of funding for consumers and businesses alike so they could weather the storm of the pandemic. What it led to was a surge of corporate borrowing and asset price growth. As a result, it is expected that global debt levels will approach $300tn by the end of this year, up a fifth on just two years ago! So now we are faced with central banks tightening policy, with debt levels up globally by 20% and GDP somewhat mixed – it may not end pretty.

After the March 2020 sell off when central banks stepped in and supplied the markets with vast liquidity, risky asset markets rallied impressively. It is logical therefore that when liquidity is withdrawn the opposite will occur, especially with many of these markets priced to perfection. Given this setup, we are very happy to run low amounts of credit risk at present, focusing on delivering high quality funds across each of our credit strategies.

Simon Prior