Game of Thrones fans would recognise the above phrase as a foreboding and ominous warning to be prepared when the North attacks. In present-day Europe, a Northern state has attacked and brought with it the threat of a very cold winter.

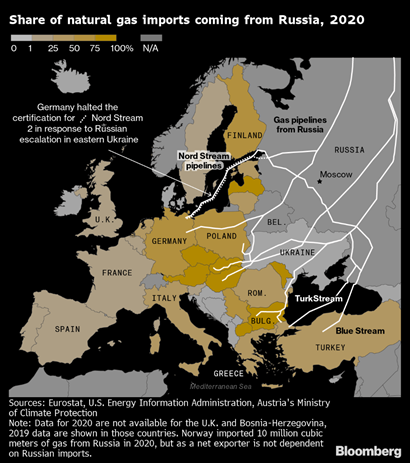

Ever since Russian gas started flowing in the 1960s, Europe has built its economies on the back of an everlasting supply of cheap gas from Russia. In 2021, Russian gas accounted for about 45% of EU gas imports and close to 40% of its total gas consumption. The share of gas imports varied with each country. Those with close proximity or direct pipelines (like Germany and the Czech Republic) had a higher reliance on Russian gas, whereas countries that were further away had other primary sources of gas and relied less on Russia. This distribution is illustrated in the map below

Gas problems with Russia began late last year and exacerbated early this year when Russia invaded Ukraine. As a result, Germany refused certification for the Nord Stream 2 pipeline (which was 10 years in the making and would have doubled gas flow capacity into Germany). Oil prices surged on the back of uncertainty of future flows. The European Commission and the International Energy Agency outlined proposals to significantly reduce the EU’s dependence on Russian gas by the end of this year and a plan to become independent from all Russian fuel by 2030. After this plan was released, EU members rushed to cut their gas usage, find alternate suppliers, increase LNG capacity, and ramp up their storage.

This plan was later complemented by the €300 billion REPowerEU plan to completely eliminate Russian energy imports. This plan focused on the following tenets – energy savings, boosting renewables, and diversifying European supplies of oil and gas. The EU also included an obligation for countries to fill their gas storage to a minimum 80% level by November. Russian supply cuts however brought unprecedented challenges to seeing these obligations fulfilled.

What is the Emergency Plan for Gas?

The Emergency Plan for Gas, which is now being applied for the first time, provides for a comprehensive set of instruments to strengthen the internal gas market in order to take precautionary measures in the event of a supply crisis. It has three escalating levels of emergency management:

- The early warning level – declared when there is concrete and reliable information that an event which is likely to result in significant deterioration of the gas supply may occur.

- The alert level – declared when there is a significant deterioration of the gas supply situation (due to gas supply disruptions or exceptionally high demand) but the market is still able to manage the disruption or demand without exceptional measures. In some countries, when this level is triggered, gas suppliers have the option to pass-on procurement costs down to customers.

- The emergency level – declared when there is significant deterioration of the gas supply in a country and extraordinary measures are needed to manage supply and demand for gas. At this level, the national grid operators are in charge of the country’s gas supplies and rationing may occur, if needed.

Eleven EU countries have activated the first stage of the Emergency Plan – Austria, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, the Netherlands, Slovenia and Sweden. Germany is the only country to have activated the ‘alert’ level, and starting from October, gas suppliers will be able to pass on additional costs to their customers, elevating the cost of living crisis.

What happens now?

Europe’s plans to reduce Russian reliance are very ambitious, but there are multiple challenges to realising those plans. Finding new suppliers is easier said than done and is a very expensive undertaking since new suppliers seek to take advantage of elevated gas prices to secure long-term contracts. The present pipeline infrastructure also makes it challenging to get gas across the continent. For instance, Spain has ample natural gas coming in from Algeria, and also regasification plants, however, there is no direct pipeline to get that gas to Germany. The EU wants to replace the volumes of natural gas with LNG, however, there just aren’t enough LNG terminals across Europe to fulfil that demand. And the distribution of the current terminals is too sporadic to effectively be used across the continent, as depicted in the example above.

Many countries are investing towards new LNG terminals, some of which are going live as early as next year. And countries are working on reducing their gas demands. Electricity production using gas plants is being replaced by firing up old and dirty coal plants. This might set Europe back in achieving its carbon neutrality goals, but the short term focus for everyone is energy security. Other measures used to decrease gas demand include municipalities turning off heating, dimming the lights and pleas to the public to take shorter showers (yes, really).

As everyone rushes to fill their own storages, they are also keeping an eye on Europe’s biggest economy. When Germany activated stage 2 level of their emergency plan, they also provided €15 billion of liquidity to secure gas supplies and established an auction system where industrial users can auction off excess gas. The marketplace goes live in August 2022 and its results will be one to watch carefully.

How has the market reacted?

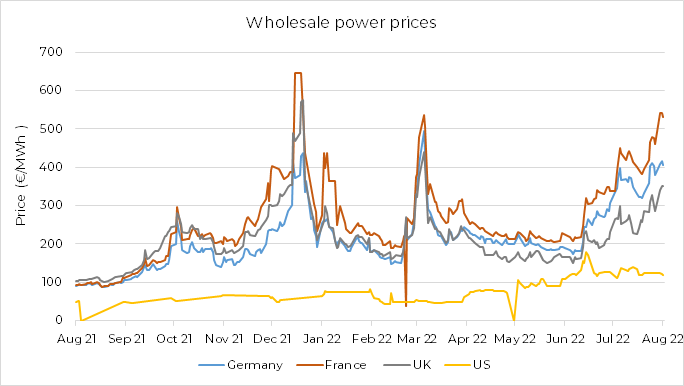

Source: Bloomberg 03.08.2021 – 03.08.2022

Power prices for Germany are 4x the price last year, which illustrates the overarching effect that this situation is having on the German economy. We can also see the steep climb in prices starting mid-June when the Nord Stream gas flows reduced. In fact, the reduced flows have almost brought prices to the same level that they were in early March. Increasing gas prices have had an especially bad effect on companies who had to buy large volumes of gas on the open market due to reduced Russian flows.

To illustrate the impact on companies, Uniper, who relied on Russia for 50% of their contracted gas volumes, had to spend around €30 million/day just to fulfil its contract obligations to its own customers. Uniper’s situation got so dire that the German government had to step in to save it.

French electricity prices have mainly risen due to massively reduced nuclear production by EDF, and the country which was once a very big exporter of electricity, has had to buy in energy to keep lights on. We can also see the UK prices graph diverging away from European counterparts due to lack of reliance on Russian gas for electricity production.

These power prices are likely to have a devastating consequence for European industrialisation. With Asia receiving cheaper oil from Russia and the US a net global exporter, power prices are likely to be a key differentiator for a while. Why make things in Europe, when you can make elsewhere and ship them in for cheaper? The cost of living is already squeezing the consumer, but with industrial companies likely to be making huge cost cuts in an attempt to remain competitive or moving their industrial bases to cheaper jurisdictions, this winter is likely to be a challenging one for people in western Europe.

Hollowing out of European Industrialisation

As professional investors we remain concerned about the hollowing out of Europe industry and as a result remain significantly underweight across the sector. The knock on impact could potentially lead to devastating consequences across the continent as governments grapple with both defense and energy security in light of the tragic events unfolding in Ukraine.