European governments will have to spend to accommodate inflation

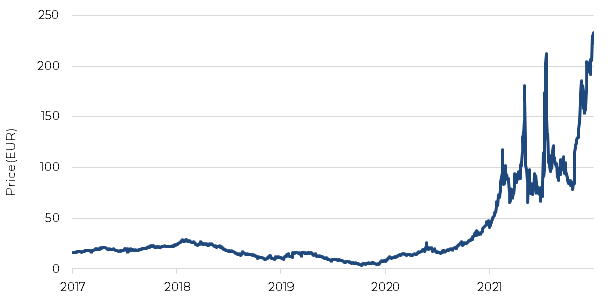

It appears that we are staring down the barrel of a gun with regards to energy driven inflation in Europe this winter. We talked back in May 2021 (The Kansas tornado – Fixed On Bonds)about the potential for kinked supply curves to emerge whereby beyond a particular level of supply constraint, the price goes parabolic. Energy has proved to be the ultimate example of this, especially in mainland Europe.

Gas hit another high yesterday (18.08.2022) in the Netherlands (Dutch TTF Gas Futures)

Source: Bloomberg, 21.08.2017 – 18.08.2022.

There are other bottlenecks aside from gas. Substitute energy costs are increasing too with the price of coal now 7 times higher than it was in 2020 and electricity prices across the bloc routinely hitting all-time highs.

As we know, the same is the case here in the UK with the cap on energy bills rising by more than £1,600 to £3,582 by October and expected to be well above £4,000 by the time we get to the next review in January 2023*, leading to expectations of a UK inflation rate peaking at 15%.

A very cold winter is on the way

Aside from struggling to heat homes because of the sheer cost, not to mention an availability issue in certain parts of mainland Europe if gas supplies from Russia continue to dwindle, high energy prices are having obvious implications for businesses too. This week we saw the mothballing of a zinc smelter in the Netherlands owned by Trafigura “until further notice”. The plant accounts for 2% of global output and is the latest in a long line of mothballed smelters culminating in Europe losing 50% of both its zinc and aluminium smelting in the past year*. European businesses are rapidly losing competitiveness versus those in the rest of the world that benefit from relatively lower energy costs.

Something needs to be done

It’s clear that supply disruption in the energy markets isn’t likely to be fixed overnight so finding alternatives to deal with the issue of very high energy prices needs to be addressed. Homes need to be warmed and businesses need to remain operational throughout the winter. Unfortunately, when we look for near term solutions, there aren’t many. But what is clear, is that all roads lead back to increased government expenditure to get families and businesses through the winter.

Large amounts of fiscal expenditure required

If you read the papers in the UK, Liz Truss is a shoe-in for No.10. Her solution to get Britain through the winter is a whopping £30bn in tax cuts. To put this in context, the massively expensive furlough scheme cost the UK £69bn. £30bn on top is another huge slug of government spending at a time when inflation is very high, meaning the Bank of England is unable to easily fire up the printing press in order to accommodate. Gilts are already starting to feel the strain of the likely economic largesse and gilt yields and UK interest rates could have further to rise.

UK purely an example of wider fiscal loosening

As we have seen in multiple crises over the last couple of decades, once one government finds a perceived successful solution, others will follow. Germany, with arguably the continent’s largest energy problem is understandably busy trying to find solutions. Economy minister Robert Habeck vowed to bailout any German energy company that falters because of Russia’s squeeze on gas supplies. We expect this type of action to be extended to all companies and similarly generous help for households. All this comes at a cost and much as we expect gilt yields to rise in the UK, the same can be said for all European government bonds as governments grapple with how to keep economies ticking over whilst the European Central Bank attempts to reduce very high inflation.

Sticky inflation

The upshot of all this is very sticky inflation as we get increased government spending at a time when governments are already increasing expenditure to change energy infrastructure and beefing up defence spending. Because governments are attempting to accommodate inflation through this increased expenditure they risk making inflation ingrained. However they have little alternative because they know their governments will fall unless they provide help to the populous.

So what does this mean for markets? Higher interest rates, less pernicious default cycle

Predictions in the UK press of higher interest rates because of increased government spending are accurate in their direction, however we believe it is highly, highly unlikely we get to 7% as some have suggested. Nonetheless, rates will go higher across Europe to deal with this accommodation of inflation by governments. The flip side of this is that whilst the squeeze is still on for businesses, leading to a long and protracted default cycle, government expenditure will mean at least some of these defaults will be avoided so there is a small silver lining, as well as keeping warm at night.