For information purposes only. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author at the time of writing and can change; they may not represent the views of Premier Miton and should not be taken as statements of fact, nor should they be relied upon for making investment decisions.

Perhaps the greatest realisation over the last 3 years for corporations and governments has been the extent to which the global supply chain is ultimately dependent on China for labour, materials, and transportation. Indeed, China has effectively exported deflation towards the western hemisphere for the last 20 years, becoming ever more dependent and addicted to cheap, manufactured goods. The pandemic, however, showcased the dangers of a single point of failure within the complex web of interdependent relationships we know as the “supply chain.” Though zero-Covid policies were not the sole cause of the trade crisis and subsequent inflation we’ve seen, the Chinese approach to virus containment was a key contributing factor that’s been felt across the world.

Add to this the cosy relationship seen between Presidents Putin and Xi, and we’re now truly in a global era of enhanced decoupling from Asia’s largest economy. In the first 10 months of 2020 the exact phrase “decouple from China” or “decoupling from China” appeared in three times as many news articles as in the previous three years combined. The world has begun a period of moving away from globalisation centred on trade and efficiency towards a fractured system of higher costs, competing technological hubs, increased constraints, and protectionism. Nowhere has this been more prominent than in the US, with laws blocking imports from China’s Xinjiang region and the CHIPS for America Act coming into effect, designed to support US semiconductor and solar manufacturing, independent R&D and a separated supply chain. Yet a question I seldom see being asked in commentary is the extent to which decoupling is even possible?

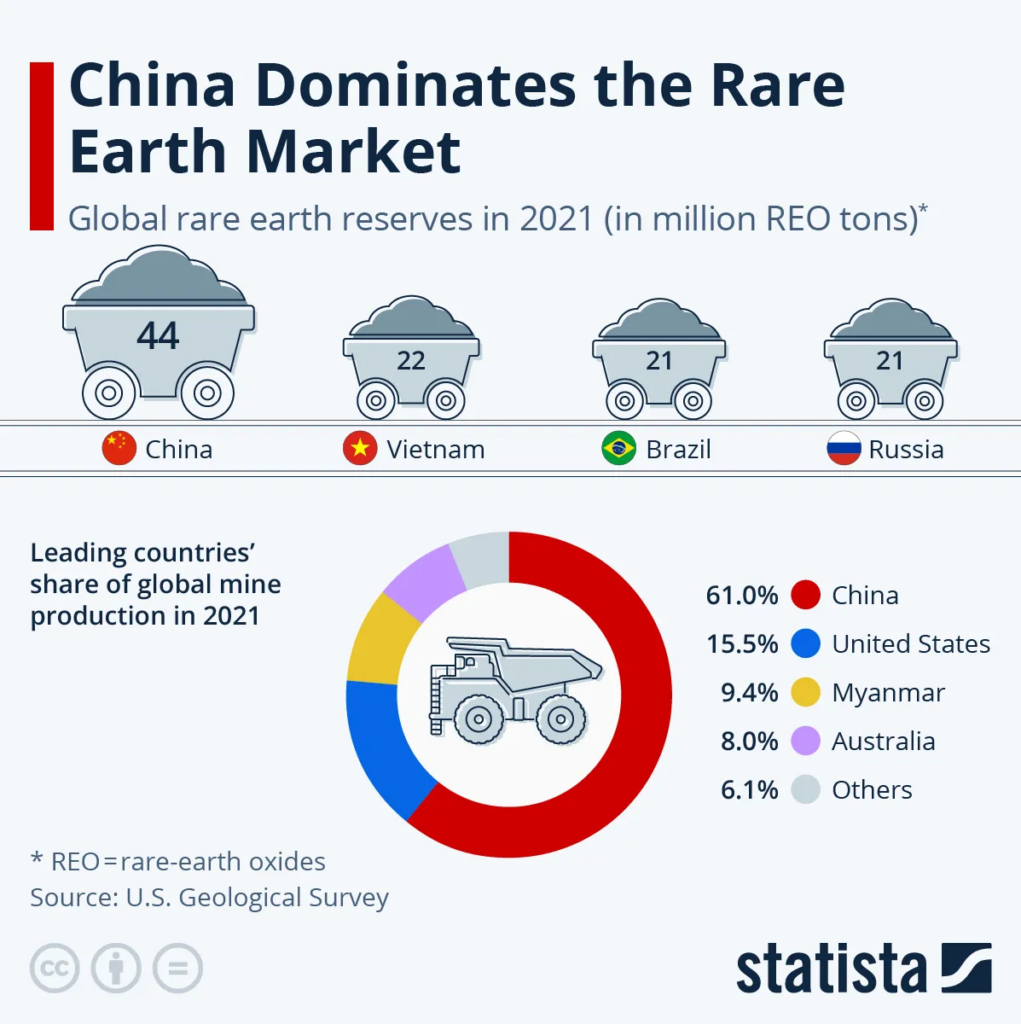

What I believe market participants are overlooking is the sheer scale to which Chinese raw materials are irreplaceable and, in its decoupling attempt, will create a higher inflationary base for manufactured goods. Looking at the chemicals sector, inputs such as adhesives, fibres, and chemical coatings are all created from Chinese raw materials at their very core. As of today, China produces 95% of the world’s vitamins and amino acids used in supplements. Furthermore, China accounts for 61% of the world’s rare earth mining, 85% of rare earth processing, and 92% of rare earth magnet production. These rare earth metals are essential in the production of wind turbines, EVs, semiconductors and solar cells.

Source: Statista

Whilst we may see companies externally move their factories away from China and towards the likes of Vietnam, Bangladesh and India, the raw materials used by said new factories are irreplaceably sourced and mined in China. In the example of rare metals, attempting to decouple from China has the potential to keep inflation elevated through significantly higher costs for renewable energy, as well as delaying global decarbonisation objectives. And we’ve seen, this was used as a political tool in the past with Japan being prevented access to rare earth elements during a 2010 dispute over Tokyo’s detention of a Chinese fishing trawler captain.

Whilst the EU have spoken this year of their desire to secure their own rare earths supply chain (something that’s 75% to 100% imported from China depending on the metal), the harsh reality is that of no alternative. And even when there is an opportunity to open mines in the western world, there can often be protests from locals and environmentalists. A proposed lithium mine in Nevada, USA, was delayed due to climate advocates. Spain have experienced public protests against plans to open a lithium mine in Estremadura. Such protests also occurred in Serbia and Portugal. And following a lengthy period of looking for investors, lithium mining is expected to start in the German state of Saxony in 2025. Yet with lithium demand expected to increase 30x by 2030, we’re only scratching the surface.

We have been discussing this on our desk for some time. If the West are serious about a Chinese decoupling, this will mean three things: firstly, significant greenfield exploration to find new materials resulting in potential environmental damage; secondly, the subsidisation of its extraction and processing to make attractive for investment and ensure cost competitiveness; and lastly, the updated regulation to make this process as swift as reasonably possible. This entire process requires higher levels of fiscal spending, the onshoring of supply chains, and significantly higher costs for raw inputs given the West’s position on the cost-curve relative to China. Of course, this is all hinged on the present rhetoric; if serious, we’re in for a period of significantly stickier long-term inflation than initially expected. With this in mind, it makes it difficult to buy duration until we see a weakening of the economy or inflation to significantly subside.