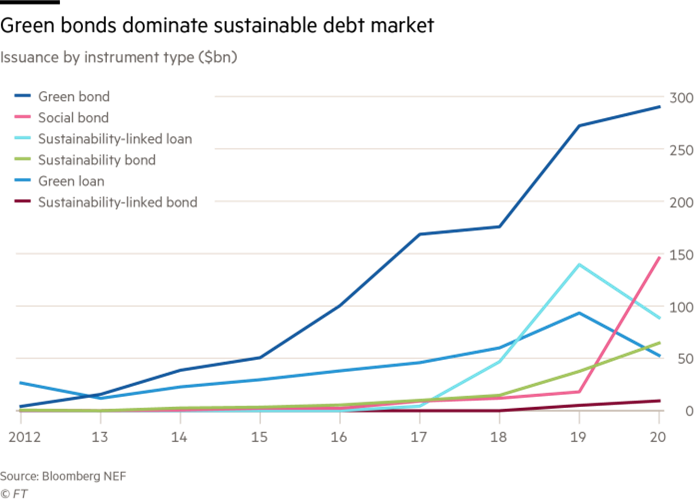

Were there a trend to define capital markets in 2020 (pandemic-induced volatility aside), I’d have classified it as the year ESG went mainstream. Of course, ESG factors have been discussed and debated for some time. August 2019 saw the Business Roundtable (BRT), a group of 200 of the largest companies in the US and generating a combined $9tn in annual revenue, drop their “shareholder first” mantra in favour of a wider, more inclusive stakeholder approach. A stark trend away from Milton Friedman’s approach which has driven corporate America for decades, the BRT emphasised the need for companies to protect the environment and treat workers with dignity and respect, in addition to delivering long-term profits for shareholders. The sharp rise in social bond issuance last year shows what I believe to be the unintended consequence of the pandemic: companies were forced to practice what they now preach.

Just last week, the Bank of England became the first central bank to begin aligning its corporate QE programme with a pathway to net-zero. This builds on the UK government’s commitment to issue green gilts in 2021. As analysts estimate that green bond issuance will reach $500bn this year (having reached $60bn year-to-date), the increasing support from global central banks coupled with staunch investor demand is likely to see ESG-labelled bonds thrive in an increasingly conscious world. As such, this market is reaching an important juncture: without some way to regulate the way these labels are used, it runs the risk of being diluted to a mere marketing exercise with minimal impact. When looking at companies, it’s essential to ensure that which is glittering is, in fact, green.

Let’s take a step back here and identify exactly what these ESG-labelled instruments are and what they seek to achieve. Green bonds, first marketed in 2008, are debt instruments whose proceeds are deployed exclusively to finance projects with clear environmental benefits, defined in Europe by the Green Taxonomy, a list of acceptable green activities. Social bonds aim to finance projects with a clear social objective, be they health, education, poverty etc. but currently lack an equivalent taxonomy. Sustainability bonds act as almost an intermediary between the two, incorporating both environmental and social aspects. Finally, a more recent development is the rise in sustainability-linked bonds, though these are somewhat of a catch-22 in rewarding bondholders through a step-up in coupon payments were the company unable to meet its own sustainability targets. The key principle aligning all of the labelled bonds is that proceeds should be used exclusively to fund their respective objective. Best-in-class ESG-labelled bonds are issued in line with the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) principles, a set of voluntary guidelines that promote more transparent, unified reporting on bonds’ environmental objectives and estimated impact.

Source: ICMA

At present, even with alignment to the ICMA, ESG-labelled bonds are but a tacit agreement saying that we expect an issuer to do what they’re intending to do with the money. Most bonds are issued under a framework document which includes commitments for enhanced reporting, however there’s rarely any legal hardcoding in the bond contract that holds companies accountable. Consequently, if businesses were to regress on their commitments, bondholders don’t generally have much power to hold them to account. This is not the case for sustainability-linked bonds, though the metrics with which these bonds are judged against can be rather opaque and difficult to measure. This uncertain nature of ESG-labelled debt further increases the importance of fund managers understanding the issuer, its positioning within the sector, and its use of proceeds to determine whether “greenwashing” is taking place.

In this regard, let me share some experiences we have recently had in the market. One potential green bond issue we reviewed was from a global glass and metals packing producer who are at the forefront of the transition away from single-use plastic, creating aluminium cans and glass bottles that further aid the circular economy. In typical circumstances, the issuer would be the perfect candidate for a green bond issuance! Where I was disappointed, however, was in their use of proceeds for this particular bond. The instruments were being issued at one entity and subsequently being sent back to the parent as cash upon divesting from an asset. Whilst the group as a whole are contributing to a more sustainable future, shareholder distributions would not typically be seen as an appropriate use of “green” proceeds.

Another issuer, a global player in wood pulp, packaging, and paper who are working with some of the leaders in consumer goods production to create products that will replace single-use plastic wrappers with more sustainable, environmentally-friendly packaging. What impressed me most was the one-to-one call I had with their management: I questioned them on their decision to not issue green bonds for their transaction, to which they replied that they would only commit once convinced that the internal measures were in place to satisfy the label. This, I felt, was a business with integrity and one I’d be more comfortable holding despite an absence of a label.

A book shouldn’t be judged by its cover, and a bond shouldn’t be judged by its label. As individuals who live and breathe these bonds and issuers daily, we’re ideally positioned to identify greenwashing when we see it. We want to do right by those who’ve trusted their money upon us to ensure that our allocation of capital is going towards a more sustainable future, label or not. All that glitters may not be green, but the grass may be greener on the other side.