The years since the Global Financial Crisis have been hard for the banking system. There has been the very obvious damage wrought upon economies from lost growth, but there has also been the less obvious hit to returns brought about by the truly enormous increase in capital that regulators have insisted upon in an effort to prevent a similar collapse ever happening again.

But the most insidious damage has been caused by the stimulatory activity, in the joint forms of quantitative easing and low (or even negative) base rates.

How so?

To explain this we need to dive headlong into a bank’s balance sheet. Fear not – it’s not that bad.

The problem is centred mainly in the traditional lending business, so that’s where we’ll look. Banks take deposits from customers, and then lend these deposits to borrowers as loans. The problem stems from the mismatch between the interest rates paid to depositors and earned from borrowers. Clearly, the difference between these two, the so called net interest income, is revenue for the bank, and in most cases is the largest element of total revenue, so is crucially important.

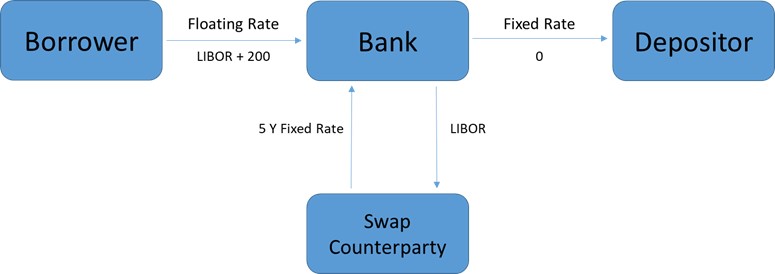

Most banks have a large element of current account balances, sometimes known as transactional accounts. These are used by customers mainly for the purpose of receiving salaries and paying bills. They are not looked on as savings accounts, and so generally do not pay interest to the customer. This sounds great if you happen to be the bank, but in reality it has a subtle problem. The interest paid on these accounts is zero and therefore has rather limited capacity to go lower. In Europe there are examples of banks charging customers for depositing money, but in the UK that hasn’t happened. The interest rates charged on loans, on the other hand, tend to be linked to short term interest rates. As an example, a borrower may pay LIBOR (or a successor rate such as SONIA) plus a spread, say 200 basis points.

The arrows show the direction of interest payments.

If the bank were to do nothing about this, it would be very sensitive to movements in those short term rates. If rates were to fall, the interest it received would fall, but the interest it was paying to depositors would remain stuck at zero. This sensitivity makes the bank unstable as its profitability swings with interest rates, something beyond the bank’s control. The regulatory response to volatile earnings might be to increase capital requirements, and so lower returns to investors. Volatility in deposit taking banks is not viewed as a good thing.

So the bank hedges its exposure. While in principle current account deposits are ‘on call’ i.e. they can be withdrawn instantly, in reality that is not how they behave. On average, deposits sit in the bank for about 3-5 years. This gives the bank the opportunity to enter into swap agreements to smooth out the rate cycles. Using the 5 year ‘stickiness’, the bank can enter into a five year swap agreement whereby it receives the 5 year fixed swap rate, and pays the three month floating rate.

In another diagram, the interest payments now look like this:

By following the arrows from the Borrower, through the bank, to the Swap Counterparty, the bank receives LIBOR+200, and then pays out LIBOR, thus fixing a margin of 200 basis points on this leg. The second leg is from the Swap Counterparty, through the bank, to the depositor, where the bank receives the 5Y fixed rate and pays out a fixed 0%, thus locking in a second margin. The bank has now immunized itself against movements in short term rates.

Of course, in the real world the bank does not enter into one 5Y swap. It enters into swaps each month, covering a proportion of the deposit base. In our example, it might enter into a swap covering one sixtieth of the deposits each month for 5 years. Then, at the end of 5 years, the first of its swaps, written 5 years earlier, will expire to be replaced by a new one. This now helps to explain why the last few years have been so painful for the banking system.

QE achieved its aim of lowering yields at all points along the yield curve, including at the 5Y point. Looking at our diagram above, that means that the 5Y fixed swap rate fell over the period. As swaps from 5 years earlier expired, the new swaps being put on were at a far lower rate, meaning that the locked in margin gradually fell as more and more swaps were replaced. There wasn’t really anything the bank could do about this phenomenon, and it acted as a multi year headwind.

But, things are at last changing. The inflationary pressure that we have talked about before has pushed up medium and long term interest rates and pulled swap rates with them. The hedges currently being put on have a higher margin than the ones that are expiring, meaning that the pressure on margins is now in an upward direction.

When we couple together upward margin pressure on the hedge, together with improved volumes of lending as economies re-open from the pandemic shutdown, the net effect is upward movements in earnings forecasts and profitability. Strong, or at least rising, profitability is a very positive development for the system and coupled with already historically high capital levels, makes investing in bank credit much more attractive again.