For information purposes only. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author at the time of writing and can change; they may not represent the views of Premier Miton and should not be taken as statements of fact, nor should they be relied upon for making investment decisions.

It is difficult to open a newspaper recently and not find an article about the much-maligned situation at Thames Water. The company are unlikely to be the next sponsors of the Oxford Rowing crew to be sure. However, it is worth pointing out the back story, how we got here, and explore potential outcomes:

Thames Water is the largest UK water and wastewater service company with a regulated capital value (RCV) of c. £19bn. We have no exposure to Thames Water within our fixed income funds, having actively avoided the name considering not only its propensity for negative headlines, but its elevated leverage, and its sizeable capital expenditure requirements.

Thames’ issues are caused by several idiosyncratic and systematic reasons. Firstly, the group were highly levered by Macquarie, their owners from 2006 to 2017. During this time, Ofwat allowed Thames’ gearing to rise from the lowest in the sector to the highest (c. 80%). As Thames became ever more reliant on debt funding to plug their negative free cash flow, and with a sizeable proportion of inflation-linked debt on their balance sheet, rising interest rates created additional strains on the group’s cash flows and credit metrics and ultimately reliant on shareholders to continually put their hands in their pockets.

Secondly, the regulators for the water industry (Environmental Agency (EA) and Ofwat) have both prioritised lower consumer bills at the expense of funding the investment needed to reduce sewage spills into rivers and seas. In the UK, both rainwater and wastewater from homes flow through the same sewage pipes. In times of elevated rainfall, and when water treatment plants and reservoirs are full, water companies are legally permitted to dump untreated sewage into rivers and seas to prevent these coming back up our lavatories! Climate change has led to the wettest years on record of late, leading to these “storm overflows” occurring more often. With the combination of nimbyism preventing the building of new reservoirs and treatment plants, elevated rainfall due to climate change, and Ofwat desiring to keep bills as low as possible, it is difficult to put the blame solely on Thames.

Lastly, given the lack of investment in the sector during the past decade, the next 5-year regulatory period (AMP8, from 2025 to 2030) is set to be the most ambitious and capital intensive. Spending is set to double to circa £100bn which will have to be funded with substantial increases in bills and debt issuance. Consequently, Thames are looking to raise £3.25bn of additional equity during the next six years to make this required spending financially viable. This brings us to the events of the last few weeks.

In July 2023, Thames shareholders said that they were willing to inject the required £3.25bn of equity provided that: 1) bills could rise by 40%; 2) the return (WACC) sufficiently compensated shareholders; and 3) the regulator would be more lenient in fining the group for environmental damages. Shareholders put £500m into Thames during 2023, with an additional £500m in March 2024 and £250m expected in March 2025.

Recent weeks have since seen a breakdown between shareholders and Ofwat over clashing priorities. Ofwat believe that Thames should be willing to inject equity at a lower WACC, whilst Thames’ shareholders want to ensure they are not throwing good money after bad having not taken a dividend in the 6 years under new owners.

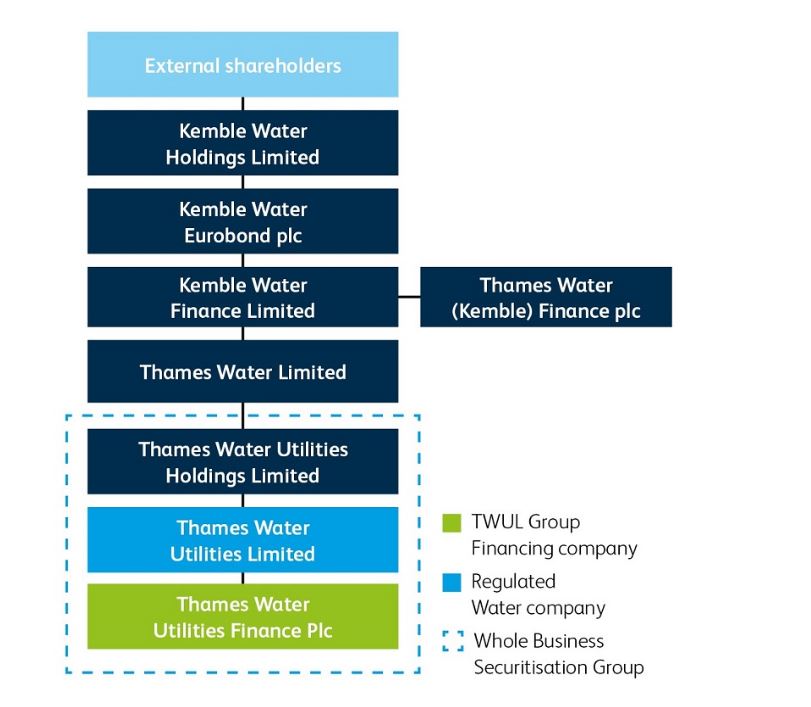

Water companies have undergone complex financial engineering to maximise shareholder returns. A simplified structure from Thames Water is shown below:

In theory, the regulated Operating Company (OpCo) entity (shown in the dotted blue line above) is immune from issues further up the chain. Kemble Water Finance Limited (Kemble), a Holding Company (HoldCo), has a £190m loan due in April 2024. Following Thames’ downgrade to BBB-, their ability to upstream dividends from the OpCo to the HoldCo is hindered and the company have announced a Kemble default to the market. Kemble lenders can now either agree to a loan extension or could become shareholders via a debt-for-equity swap which could zero existing shareholders.

With Thames still requiring an equity injection of >£3bn, and the OpCo having only c. 15 months of liquidity left, financing will need to come from somewhere. If existing shareholders refuse to inject further cash, and new shareholders cannot be found, a Special Administration Regime (SAR) is triggered with the government responsible to find a new owner. In a SAR, the assets of Thames are “hived down” into a new structure which leaves existing OpCo bondholders stranded. A new equity investor is likely to need to be heavily to be incentivised to take on the name and, based on the clearing price received for Thames, existing lenders to the OpCo could face a haircut or even a wipe-out depending on the seniority of their investment.

This last situation has been the key concern of creditors. Despite investors scrambling to determine the likelihood of potential outcomes, there exists glaring known unknowns: i) at what discount to RCV will the government be able to find a buyer; ii) how much will the government loan to keep Thames operational in a SAR?; iii) at what capital structure and gearing will Thames NewCo exit the SAR with? Without knowing these, any investment in Thames bonds remains highly speculative.

This entire situation is textbook game theory. All parties are aligned in wanting to find an outcome and SAR remains very last resort for the government, Ofwat and shareholders: A nationalisation of Thames during an election year would be difficult to swallow for a Conservative government who have so far defended Thatcher’s legacy; SAR would bring Ofwat further into the spotlight with many questioning how a “world-leading” regulator allowed/encouraged increasing leverage during the last 15 years; and Ofwat is keen to encourage investors to continue to inject essential capital into the sector, all without creating a moral hazard of allowing badly run companies to be seen to be bailed out.

Given the significant capex that is to be funded through new debt and equity, we believe that Ofwat will certainly make some concessions from their “early-view” WACC. It does not seem sensible to scare away potential investors when new equity and debt is essential in financing the large investments mandated for the sector. Contagion risk in the sector remains; the collapse of Thames would increase debt costs for all water PLCs. That said, given public scrutiny of late, Ofwat cannot be seen to make many concessions and must be perceived as having driven a hard bargain. This all seems like a delicate dance.

The outcome for Thames and the wider UK water sector remains wildly uncertain. As credit investors, our priority focuses on downside protection; we believe that any financing into the space, and into Thames specifically, constitutes a speculative bet rather than a sensible investment. Our funds are run with a quality bias – everything that Thames isn’t. An incoming Labour government further increases the risk of a full loss to OpCo bondholders. We remain happily on the sidelines.