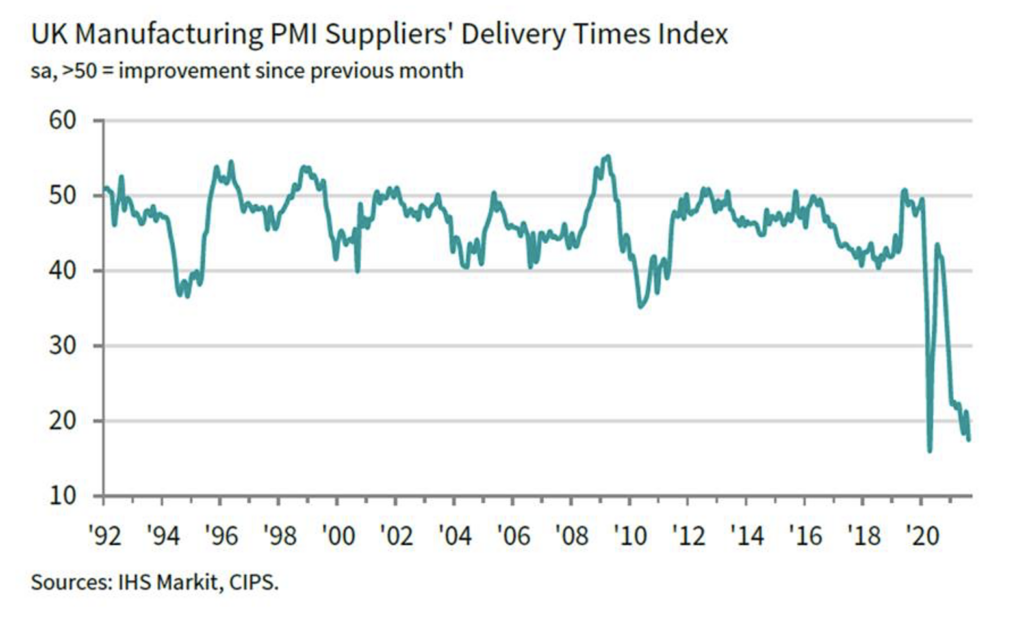

We talked previously about our worries that in the short-term, inflation is likely to be an issue for the global economy. And we are still very worried – worried that supply disruption induced “transitory” inflation could last well into next year and possibly even 2023, slowing the global economy. This week the PMI surveys out of the UK, which incidentally painted a picture of slowing activity, showed supply constraints starting to bite, no more so than supplier delivery times seemingly heading to April 2020 lockdown highs as global supply chains are crippled by the delta variant:

As we talked about some time ago in Shot Induced Shortages there is currently a juxtaposition between developed market economies that are way ahead with their vaccination programmes and getting on with reopening, and emerging markets which are lagging with vaccinations and are behind in getting economies moving again. To add to this issue we have the response from authorities in certain countries, including China, trying to keep covid cases at zero. This is clearly very difficult to achieve given the speed with which the delta variant transmits. What’s more, this type of response is exacerbating supply chain disruptions from those countries that produce, such as China to those that consume, primarily the West.

The response to this disruption will be more automation

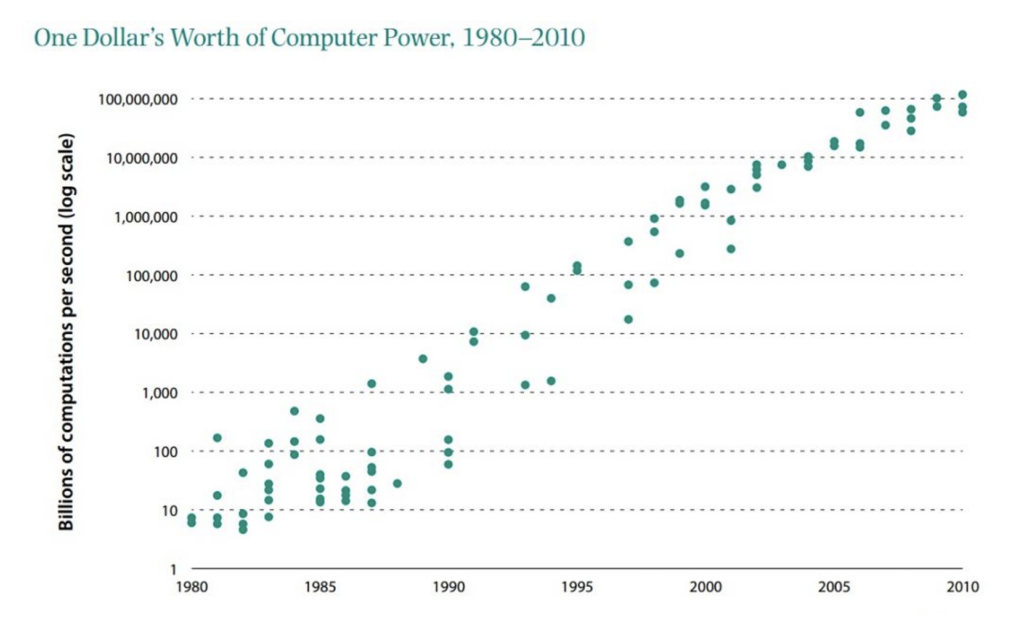

Much of this supply disruption is clearly coming from a lack of available labour, which is spurring on companies to automate more rapidly than they previously were. From McDonald’s to the mining sector the aftermath of the pandemic is seeing companies look to reduce the risk of labour force disruptions through increased use of technology. This is another example of a trend being accelerated by the pandemic, driven by technological advancement continuing along its exponential path:

Source: Hamilton Project, 19 February 2015. Source: Nordhaus (2007); updated data through 2010 form Nordhaus, personal website, http://www.econ.yale.edu/-nordhaus/hompage/.”Two Centuries of Productivity Growth in Computing.”; authors’ calculations. Note: Nordhaus (2007) defines computer power as the rate at which computers and calculators can execute certain standard mathematical tasks, measured in computations per second. The data have been adjusted for purchasing power to year 2006 dollars

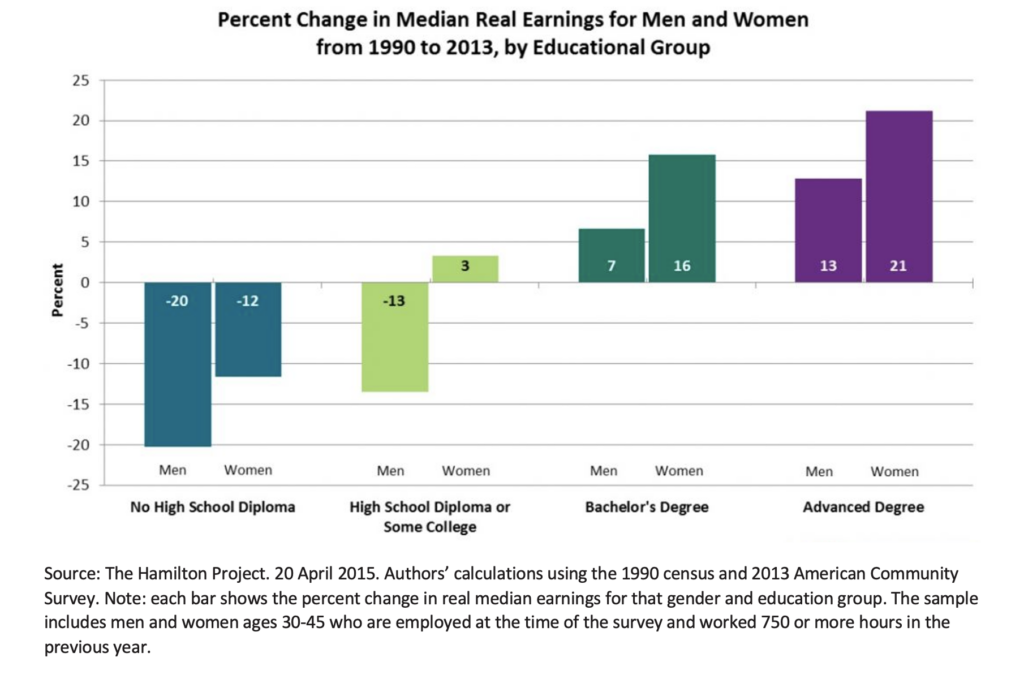

But there’s been a price to pay for this advancement and it’s fallen at the feet of the least educated with wages struggling to keep pace with inflation as jobs at the bottom end of the education spectrum have been destroyed:

Once we work through the labour supply issues we see at present, the response to the pandemic may actually be less jobs not more, driven by technological disruption and robotics. And as more technological advancements are made through robotics and AI, wages are capped further up the education spectrum, thus dampening inflation throughout the economy. Whilst wages are only one component of inflation, they are an important driver if it is to be sustained. This clearly has implications for markets, particularly fixed income and put together with the greater debt burden because of the pandemic, this means the peak of interest rates in the next rate rising cycle is likely to be lower than that in the last.

Lloyd Harris