It’s impossible to imagine our life without it. Durable, lightweight and cheap, plastic is a fundamental part of our existence. Having been around for a century or so, the material’s rise to prominence has largely been in the past 50 years and has become a booming industry. Indeed, the plastic bottle industry alone in the US is today worth c. $25bn. And let’s not forget that plastic has been essential in enabling the technological revolution we all benefit from today, in saving lives through improved hygiene standards within healthcare, and in the transportation of people and products across the globe! It was and continues to be, a miracle material.

Yet, as it appears time and time again with humanity’s innovations, the negative externalities of the material are all too well known (cue images of floating plastic islands in the Pacific Ocean and turtles with plastic straws stuck in their noses). With COP26 just having passed, I thought to share what I feel to be the two main problems with plastic, based on speaking with company management within the space.

Recyclability

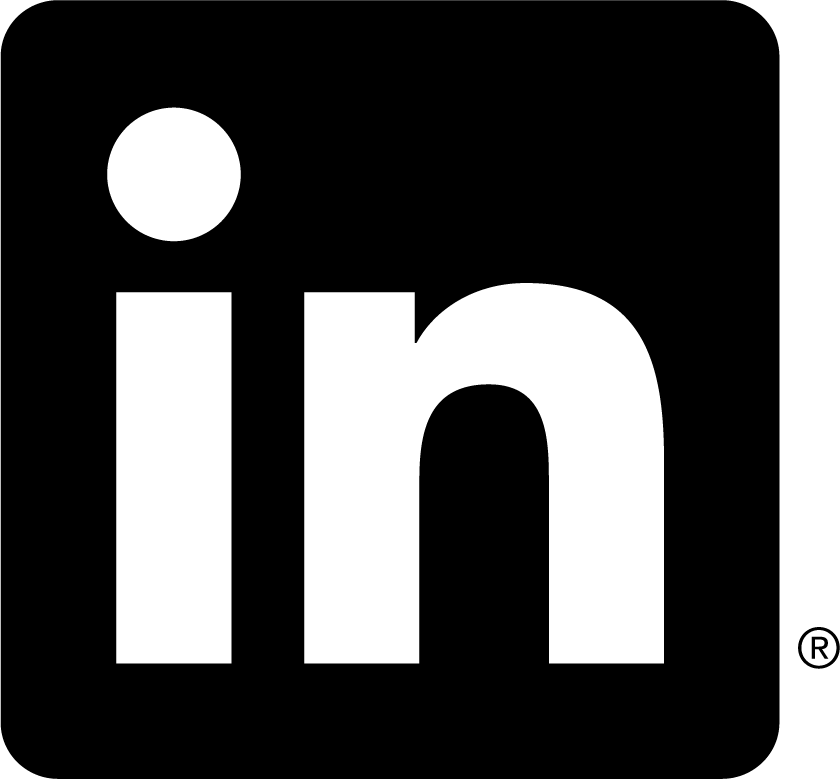

There are many facets to the problem of plastic recycling, but the recyclability of the material itself isn’t one of them! The manufacturers of plastic bottles pride themselves on their product being as recyclable as aluminium and glass packaging, for example. The issue lies in the subsequent collection, treatment and processing of plastic waste. Historically, plastic collection has been expensive for two reasons: 1) consumer habits have tended towards disposal rather than the recycling of plastic; 2) due to mechanical recycling technology being preferred, plastic can only be recycled into low-grade products and have a limit to their recycling cycle. This has led to just 16% of plastic waste being recycled to make new plastic with 40% sent to landfills. Furthermore, most of the plastic that does get sent to landfills could have been recycled were it not for slight contamination making them unsuitable to be recycled under existing technology.

Where there is a change, however, is in the transition away from mechanical to molecular (chemical) recycling technology. Instead of a system where some plastics are rejected because they are the wrong colour or made of composites, chemical recycling could see all types of plastic fed into an “infinite” recycling system that unmake plastics back into oil, so they can then be used to make plastic again. We see this occur with other materials. Aluminium cans, for instance, are 100% recyclable with 70% of all aluminium manufactured still in circulation today. It appears as though the evolution of technology is the key that could unlock this problem. Not only will this lead to almost all plastic being available for recycling, but also waste plastic becoming a resource and a raw material that is compensated adequately for its collection.

I recall a recent call with Aliaxis, a global manufacturer of plastic pipes for industrial end markets. They spoke of their desire to use more recycled materials to create their end product but regulation prevented them from doing so. The evolution of chemical recycling could lead to a seismic change in regulation, alleviating concerns of mechanical recycled plastic’s degradation of quality relative to virgin plastic.

Substitutability

Plastic is both incredible and potentially treacherous for its inherent quality of durability. It’s a material that can be found in the earth, the air and in the depths of the ocean. Its durability is such that the majority of what has been created still exists within our ecosystem! We’ve created a society that’s fundamentally dependent on this miracle innovation. You’re perhaps reading this piece on your computer, wearing your finest polyester shirt whilst brewing your favourite tea bag. The root of the plastic problem, however, is this: we don’t have a viable alternative. What we are seeing is a resurgence in paper-based packaging to replace single-use plastic in whatever way they can, particularly within FMCG. However, consider the following:

Imagine you’re in an airport desiring to quench your thirst just before the boarding of a short-haul flight. You purchase a beverage of choice and throw it into your bag containing your valuable documents, laptop, and personal items. Out of the variety of packaging options at hand, the one that would be most suitable is a plastic bottle! Not only is it unlikely to be damaged and leak than its alternatives, but it is also the only bottle you’d trust to maintain a tight reseal required so as to not damage one’s valuables. This is but one example to prove the real issue at hand: a lack of substitutability. According to the Plastics Industry Association, plastic bottles and jars represent about 75 per cent of all plastic containers, by weight, in the United States.

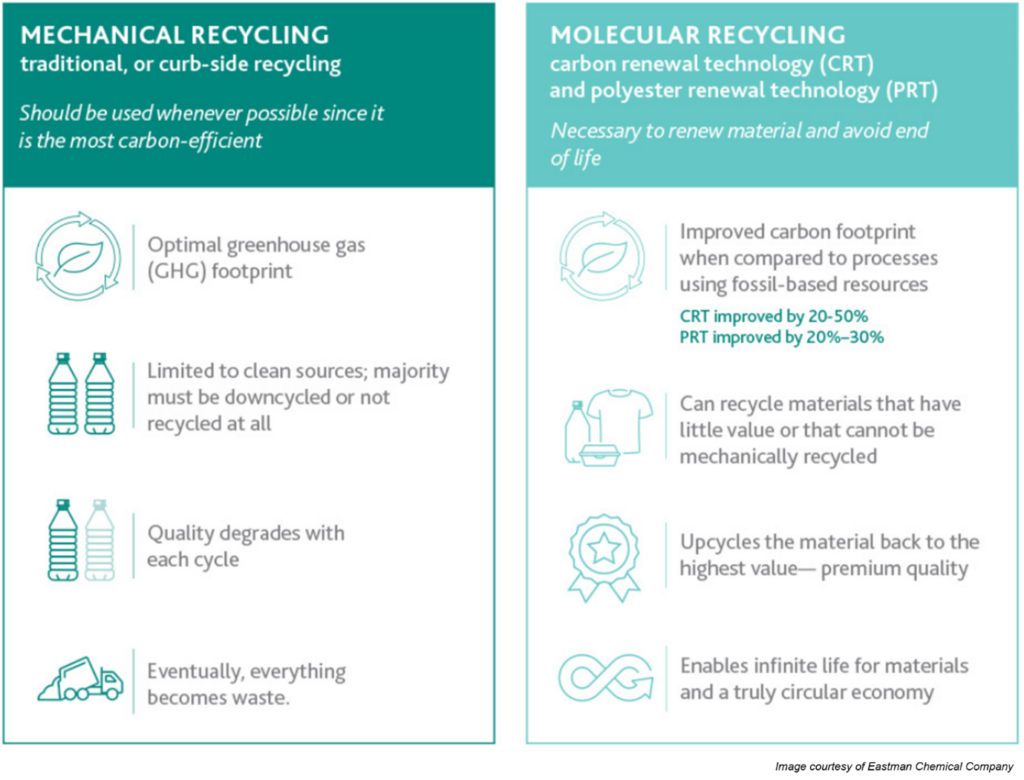

One common argument to further substitution away from plastic is to criticise the emissions produced through the manufacturing of plastic. Aluminium, for example, produces nearly 30% more emissions than plastics. Iron, steel, and concrete also emit up to twice as many emissions during production as plastics and have other environmental impacts like high water usage and lack of end-life opportunities.

Global Warming Potential (g CO2 eq/liter)

Created from: Life cycle environmental impacts of carbonated soft drinks. David Amienyo & Haruna Gujba & Heinz Stichnothe & Adisa Azapagic Published 03.07.2012

When we speak of investing responsibly, it requires a framework for thought and analysis. I believe that it’s important to be pragmatic; society knows where it wants to be concerning the use of fossil fuels, but this requires a journey of transition towards the goal. Until now, more sustainable materials are created to aid transitions away from plastic, society’s dependence on the substance is likely to continue in some shape or form.

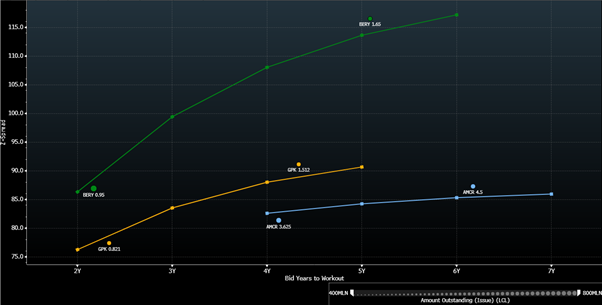

Amcor, Berry, and Graphic Packaging Pricing Spread

Source: Bloomberg.

What we increasingly see is a price differential between highly-rated ESG names and the not-so. Let’s take the above, looking at Amcor (BBB, light blue), Berry (BBB-, green) and Graphic Packaging (BBB-, orange). Amcor is seen to be a leader in the field. Being rated AA by MSCI for ESG, the group have pledged for all of its packaging to recycled, compostable, or reusable by 2025 and sources half of its energy from renewable sources. The group continues to lead in innovation, recently creating solutions to previously unrecyclable microwavable and pet food pouches. It’s this kind of innovation that appears to be rewarded by investors. Their closest peer, Berry, despite only being rated 1 notch lower and having similar profitability and leverage metrics, trades almost 40bps wider than the equivalent Amcor bond at the 4-year mark. A key reason for this appears to be the group’s lagging ESG metrics, for if it were purely a rating issue it would trade in line with Graphic Packaging. Plastic is already a sector that investors may shun for fear of client backlash and whilst Berry are by no means a significant laggard in ESG, the difference is noticeable and it appears to be a key driver for the significant difference in pricing.

As I previously wrote of how minerals are essential for the move towards net-zero, firms enabling a more circular use of plastics through reusability and recycling are essential towards the change. The solution isn’t the demonization of plastic or all things carbon. Whilst this may help generate traction towards the problem, it doesn’t deal with the practicalities of a transition. The solution will evolve over time, I’m sure. Through education to change consumer habits, deployment of new recycling technologies and the eventual development of substitutes, we may create a system whereby no new virgin plastic needs to be made. Until then, we seek the change-makers!